4 Ways Your API Is Not Quite What I Want

There are thousands of APIs. That means that there are a lot of bad APIs. More importantly, there are many good APIs. We can learn from both, as you look to enable what developers (and the users they support) need from your API.

At its basic level, an API is really just a way to transfer data. But by transmitting this data, APIs also expose the functionality of the apps they support, and sometimes that can make it tough for a developer’s use case to also be supported. An API that’s not quite what the developer wants is enough for your API to get passed over, an opportunity for integration lost.

After evaluating hundreds of APIs in my career as a tech journalist and developer advocate, I have seen these four frustrations below across dozens of APIs. Though I call out a few specifically, I’ve tried to keep the descriptions general enough that you’ll be able to see your own API in these examples. And if it makes sense, I hope you’ll adjust your API to provide the data that developers want, in the way they want it.

1. Your API Gives Me Too Much Data

Too much data is not the worst thing an API can do. (The worst thing is probably to provide no data or for an API to not exist at all). When there’s data available, you’re at least able to access it. However, to get at the data they want, developers might have to write additional code. Both developer and API provider must accept the inefficiency of transferring 90% or more of the data that is never used.

Too much data situations often represent themselves with endpoints that look like this:

/api/widgets: lists all widgets owned by the account

Now, that’s a perfectly fine endpoint, as long as accounts typically contain less than 20 or so widgets. Beyond a couple dozen widgets, however, the endpoint better be followed by some comprehensive search options. What if I just want to find green widgets? Or widgets by a certain manufacturer or with a specific name?

Without some sort of filter option, developers need to loop through the results and make the comparison themselves. It’s annoying, but developers are used to writing loops. What if the account has thousands of widgets? It’s either one big download (which hopefully doesn’t timeout) or developers have to write another loop to go through multiple pages of results–and multiple HTTP requests, where one may have sufficed.

Too much data isn’t just an issue with pulling data from APIs, it also can arise from webhooks. We’re a big fan of the subscription webhook design pattern, where an application registers to receive notifications of new data. Even this efficient way of receiving updates can send too much data. Webhooks are a great situation to get granular with what kind of data to send. Yet, sometimes there’s a single webhook that sends updates whenever anything in the account changes.

Again, there are workarounds like manual filters for too much data. The same can’t be said for too little data.

2. Your API Won’t Just Show Me Everything I Need

Do developers want it both ways? No. Developers want it all ways.

When you’re used to controlling every aspect of an application, you want to continue the same with an API. However, APIs typically support many applications, which means many different use cases. Providing a means for flexible API responses is one way to enable developers to support their use cases. Another is to only require parameters that are absolutely necessary. Any required parameter might limit the results available to a developer.

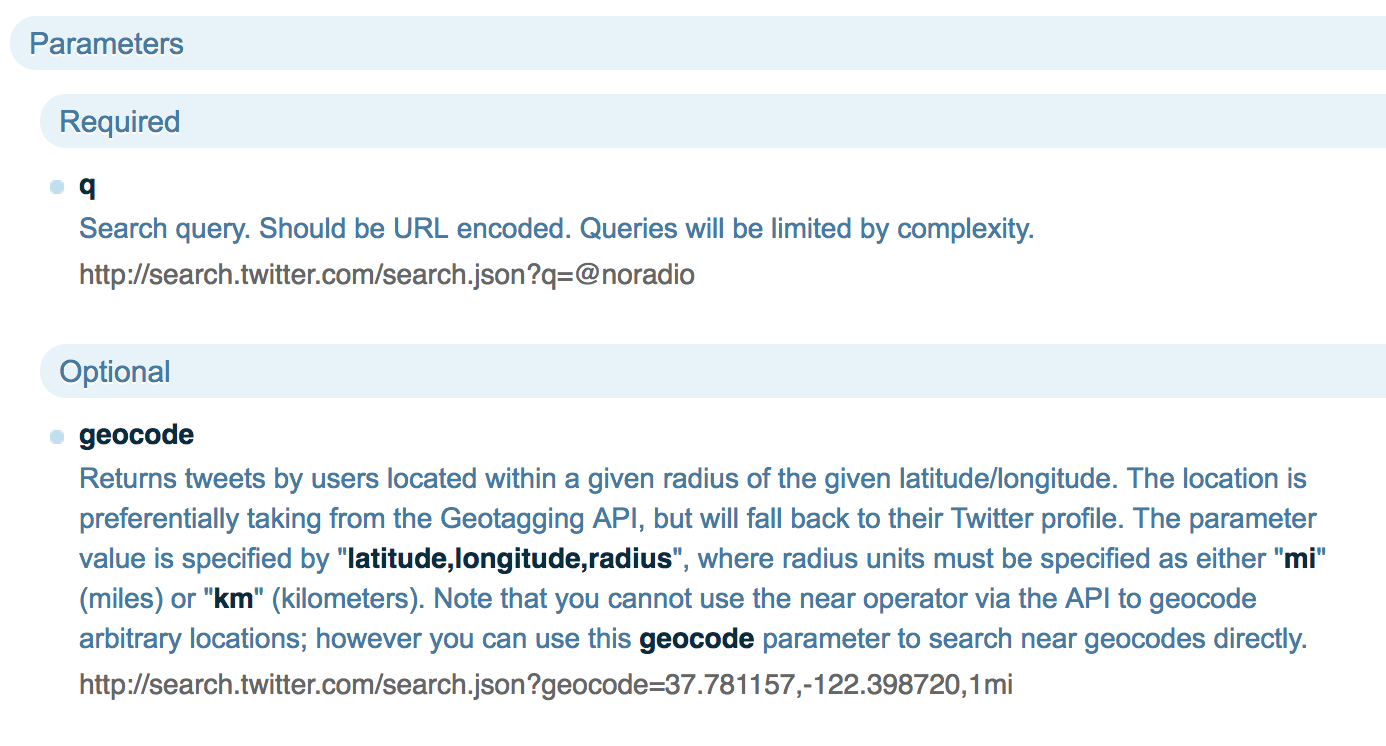

For example, Twitter used to require a search term in addition to the location for its geocoded Tweet search. Developers who wanted to track every location-sharing Tweet from their own neighborhood needed to search for some keyword, in addition to a center point and radius. By searching for a keyword, of course, they’re not getting every nearby Tweet. Perhaps based on developer complaints, the current version of Twitter’s search API now supports the keyword-less location search.

Sometimes there is a strategic or technical reason for requiring a filter. For example, GitHub code search gives developers programmatic access to text search all the code on GitHub. That’s a lot of code! As such, GitHub has a few restrictions:

- Unauthenticated requests must include a user, organization, or repository

- All searches must include a search term

The latter is similar to Twitter’s old requirement, keeping developers from unfiltered code results in metadata searches:

You must always include at least one search term when searching source code. For example, searching for

language:gois not valid, whileamazing language:gois.

GitHub likely has good reasons for this requirement. A developer API for a developer service is likely to make as developer-friendly choices as they’re able. As you consider required arguments that might limit the results, ask yourself whether there are good reasons for the restriction.

3. Your API Has Only One Way to Search

The reason so much of this post has been about searching and filtering is that those are the primary ways to alter API responses. Sometimes APIs will provide search options (yay!), but they aren’t the ones required by a developer’s use case (boo!). It can be helpful to give developers multiple vectors to the data they’re searching.

For example, let’s say your API provides access to some kind of calendar/event tool. You might have an endpoint like this:

/api/events/?startdate=2017-03-31&enddate=2017-04-01

Anyone looking to search your events by date would be set: just specify a date range and you’re good.

What if you want to find all the events for a particular user? Whether it’s an actual calendar, a scheduling app, or an event ticketing tool, there is usually a concept of an attendee. If date is the only way to search events, then we’re back at problem #1 above, manually filtering out all events without a particular user attending. Even worse, depending on the API design (and the number of attendees events usually contain), we may need to make a separate API call to retrieve each event’s guest list.

We can see similar issues in other types of APIs that have users but are centered around objects other than the users. Shopping carts can have this issue. An order contains a list of items, a subtotal, a total, and some other metadata. In a shopping cart’s database, the user is stored separately. A shopping card API will likely allow you to search by that same data, but cannot go the other way to find all of a particular user’s orders.

Often, these problems arise when your API is built around how you model the data, rather than how your developers want to consume it. Find out who actually uses your API, determine the use cases they need, then build the API features needed to support them.

4. Your API Requires Multiple Calls for One Action

The shopping cart example, where finding a user’s orders is not directly supported in the API, can also complicate things when creating new orders. And this is not just an issue for shopping carts. Accounting software (with expenses and vendors tracked separately) and email marketing (with email lists and subscribers kept separate) are other examples.

Some APIs require two separate calls, one for each type of data:

- Create the “inner” data, such as a contact

- Create the “outer” data, such as an order or adding the person to the mailing list

Treating these separately in your own systems makes perfect sense. It’s good database normalization. It might even make sense to have separate endpoints to create the inner and outer data. However, if developers are often making both calls, it also makes sense to provide a way to do so with a single API call.

In fact, you may not even need a third endpoint to achieve this. For example, when adding a contact to a mailing list, you could allow either a contact_id or email_address. If the email address is sent, presumably you’d create a contact (with a contact ID) behind the scenes and perform the association.

Developers using your API don’t need to know how you store your data.

Talk to Your Developers and Users

The only way to know what developers want is to ask and listen. Further, you should consider more than what developers want–you should make sure you know what your users want. Their needs will also drive the needs of developers.

Often an API is built only around an internal use case. Dogfooding is important, but your use case won’t always fit with others. For example, maybe your API supports your mobile app. Retrieving all the data once then only syncing changes is a good way to conserve bandwidth. However, that’s not going to have all the slicing and dicing of data that other use cases will require.

The four issues mentioned in this post are overlapping and even a little bit contradictory. Your users can give you the additional information needed to know which of the above situations apply to your API. Look at your API framed around what your users are trying to accomplish. Then make sure that your API easily supports those use cases.

One great way to take a user-first approach to your API is to build a Zapier integration. Our free developer platform connects your API to over 1 million Zapier customers. Build Triggers (new data available to a user), Actions (data the user adds, often from another system), and Searches (lookup a specific record) to connect your API to 750+ other applications.

Comments powered by Disqus