Productivity tips

6 min readHow to write real good

By Hannah Herman · July 2, 2021

Get productivity tips delivered straight to your inbox

We’ll email you 1-3 times per week—and never share your information.

Related articles

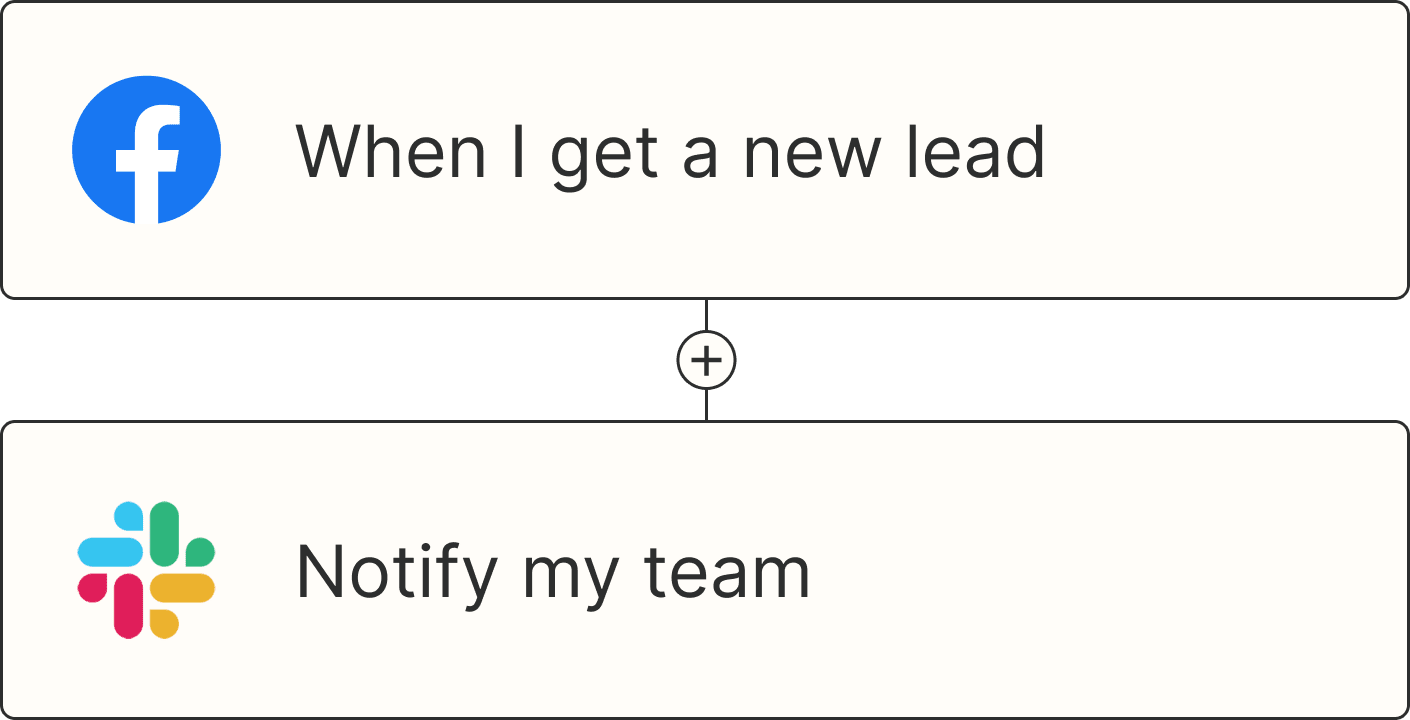

Improve your productivity automatically. Use Zapier to get your apps working together.