Business tips

6 min read4 Rules of Improv and How They Relate to Customer Support

By Micah Bennett · December 3, 2015

Get productivity tips delivered straight to your inbox

We’ll email you 1-3 times per week—and never share your information.

tags

Related articles

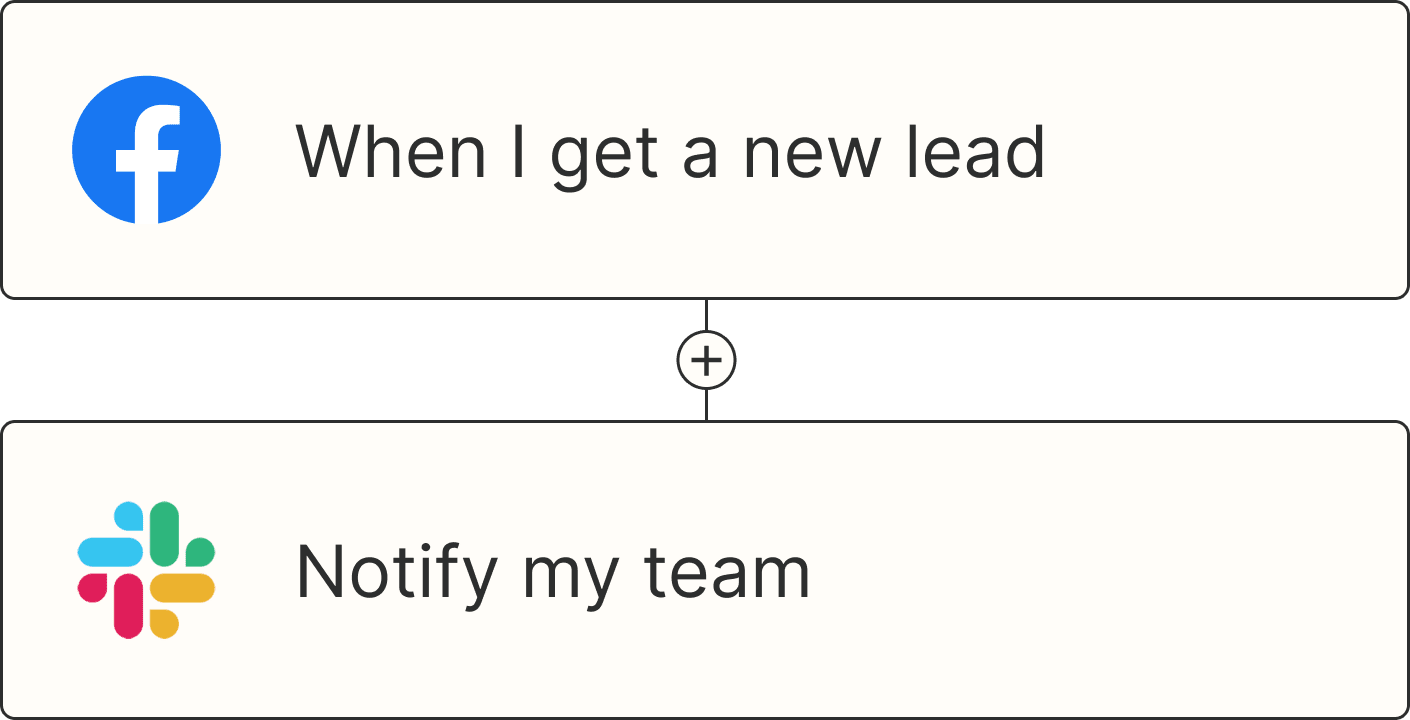

Improve your productivity automatically. Use Zapier to get your apps working together.